Atoms bind to each other by exchanging or sharing electrons.

The "tufa" towers that rise from Mono Lake in California are composed of a wide variety of salts, combinations of ions that wash down from surrounding mountains into the lake. The line between ionic and covalet bonding (the difference between complete transfer of electrons and sharing of them) is a fuzzy line.

Review of ionic bonds

In another section we learned about ionic bonding. We know that certain atoms tend to either gain or lose electrons in order to build or reveal a filled valence shell. This tendency toward energetic stability means that elements in the first and second groups of the periodic table form +1 and +2 ions, respectively and elements in the 6th and 7th groups form -2 and -1 ions.

The electrostatic force (opposite charges attract) then binds these ions together in an ionic compound in which

elements exist in certain well-defined proportions, ratios that ensure that the sum of all charges is zero — or that the overall charge is neutral.

We noted that ionic compound formulas don't represent single molecules, but rather formula units. For example, the formula for sodium carbonate, Na2CO3, says that in any mass of sodium carbonate there are two Na+ ions for every one CO32- ion. We never actually find a single Na2CO3 molecule, just a chunk of sodium carbonate in which there are two sodiums for every one carbonate ion.

Covalent bonds

Ionic compounds form because one or more electrons transfer completely from one atom to another, making a positive-negative ion pair. But the majority of chemical compounds form when two atoms "share" an electron in order to complete a valence shell in each. These are not ionic compounds.

The chemistry of carbon

As an example, let's think about carbon, which contains four electrons in its outer shell, two in its 2s subshell and two in its 2p subshell.

Carbon needs to gain four electrons to have a full octet. It can do this by bonding with four hydrogen atoms, each of which has one electron, just one short of a full 1s shell (remember, H never gets an octet).

The situation is pictured below. When the bonds are formed (right), the carbon atom is effectively surrounded by eight valence electrons, all occupied in the four C-H bonds, and each hydrogen is associated with two electrons, one its own and one from the carbon. The valence shells of each atom are in this way complete and this molecule, methane, is very stable.

Covalent bonds are bonds that complete or partially complete the valence shell of each atom in the bond through the sharing of electrons. Thus, the term co-valent.

The actual picture is somewhat more complicated...

If you're just learning about covalent bonding, you might want to skip this section and the figure below. You can come back to it later.

When atoms that form covalent bonds come together, what actually happens is that the valence-shell orbitals of each rearrange to produce a different set of orbitals – molecular orbitals instead of atomic orbitals. The molecular orbitals have the same capacity to hold electrons as the individual atomic orbitals from which they were formed.

The picture below shows how the s and p-sub orbitals of C and H come together to build two sets of molecular orbitals, which we call the bonding molecular orbitals (BMO) and the anti-bonding molecular orbitals (ABMO).

You might notice that a hydrogen atom doesn't actually have p-orbitals - why would it with only one electron? But remember that orbitals are formed by electrons (and don't exist when they're not there), and when the electrons of four H-atoms and one carbon combine, the need for p orbitals in H is created.

In general, the electrons that form bonds remain in the BMOs because they are of lower energy and therefore more stable.

There is much more to molecular orbital theory than I can present here, but I wanted to give you some background about this "sharing" of electrons.

Covalent & ionic bonding: How to tell the difference

Atoms bond as groups of ions (usually pairs) or they bond covalently by sharing electrons in bonding orbitals. How can we tell how two atoms will bond ahead of time?

One way is to use electronegativity, which we discussed in the periodic trends notes. Electronegativities of the elements can be calculated according to a formula developed by Nobel Prize-winning chemist Linus Pauling (Pauling was the only person to ever have won two Nobels, one in chemistry, the other the Peace Prize for his work to stop the nuclear arms race). I won't go into the detail of Pauling's calculation. The Pauling electronegativities of most of the elements are given in red in the periodic table below.

In general, when the difference between electronegativity of two atoms is large, they will tend to bond ionically. When the difference is small, they'll bond covalently.

You've noticed that I haven't said what "large" and "small" actually are. That's because there are always atom pairs that fall somewhere between ionic and covalent bonding. We'll cover those later. Nevertheless, there are a couple of accepted rules.

Example: NaCl

Looking at the table below, we see that the electronegativities of sodium (Na) and chlorine (Cl) are 0.93 and 3.16, respectively, for a difference of 2.23, so we'd expect these atoms to bond ionically, which they do.

Example CH4

The electronegativities of C and H are 2.25 and 2.20, for a small difference of 0.05, so we'd expect these atoms to bond covalently, and they do.

It's a little tricker when the electronegativity falls into that in-between area.

Example H2O

The electronegativities of O and H are 3.44 and 2.20, respectively, for a difference of 1.2. It turns out that the covalent O-H bonds in water have significant ionic character. In water the oxygen atom shares an electron with each hydrogen, but the bonding electron pairs are strongly drawn toward the oxygen, leaving a mostly-bare proton sticking out. That's part of what makes water such an interesting and unique substance. It's why it is polar (has distinct negative and positive "ends") and why it forms hydrogen bonds. See the notes on water for more.

We will look at many more examples of bonding below.

You won't always have to jump to electronegativities to decide whether a bond is covalent or ionic (or some of both). Most of the time the bonding will be clear because of context, and because you'll develop an instinct that comes from memorizing a few important ions and a few structures of some important covalent compounds, like water, methane and ammonia.

Examples of covalent bonding

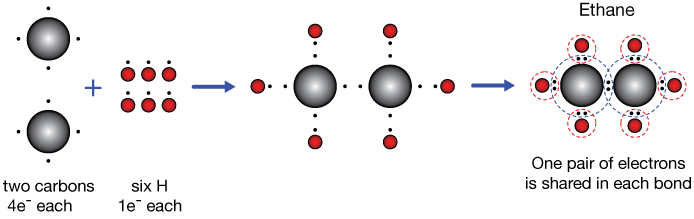

Ethane C2H6

Ethane, C2H6, is a hydrocarbon molecule, an odorless gas at room temperature. The covalent bonding picture of ethane is very similar to that of methane above. Two carbon atoms, each carrying four valence electrons, come together to share a pair of electrons. We'll start calling that a single bond (or sigma bond).

That leaves six unpaired electrons on the C2 unit. Each of these is paired with the single electron of a hydrogen atom to give each carbon a stable valance octet (dashed circles on the right), and the valence 1s shell of each H-atom is completed by sharing a single electron from a carbon.

A single or sigma bond is formed by the sharing of two electrons between atoms. Those electrons mostly occupy a space between the two atoms.

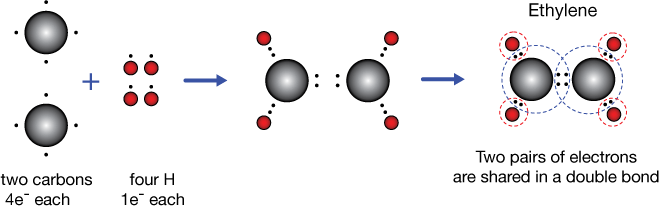

Ethylene (or ethene) C2H4

Ethylene is a colorless gas at room temperature, and is composed of two carbon atoms and four hydrogens. Ethylene is a precursor in a wide variety of chemical synthesis reactions, including formations of long chains of ethylene molecules called polyethylene — a plastic.

If you review bonding in ethane, the previous example, you'll notice a problem. How can we expect C2H4 to bind together like C2H4, when we'd be "missing" two hydrogens? Wouldn't we have two unpaired electrons and some non-octets? There's a way to do it.

In ethylene, each carbon shares two of its valence electrons with the other carbon, forming a bond that contains four electrons that we call a double bond or a pi bond. In this way, each carbon "sees" six electrons just from carbon atoms, four of its own and two from its neighbor. Further pairing of the remaining two unpaired carbon electrons with hydrogens fills up all valence shells nicely.

Acetylene (or ethyne) C2H2

Well, why not triple bonds? In acetylene, one of the two gases involved in oxyacetylene welding, we only

have two hydrogen atoms to bring in extra electrons, so each carbon must share three of its four valence electrons with the other in order to form valence octets. The result is a very strong triple bond. Here's how it looks.

Shorthand drawings

The molecules we just studied as examples can be represented by stick figures like these →.

Each single bond gets a single line. Double bonds get two and triple bonds get three. Each line represents a pair of shared electrons.

Once you've got the hang of this section, you should move on to the notes on Lewis structures, a helpful method for determining what kind of covalent compounds can form from selected atoms.

Bond lengths and strengths

A few key factors affect the relative strengths of chemical bonds. They include

number of electron pairs shared (single vs. double vs. triple bonds),

neighboring bonds to other atoms

geometric strain

resonance bonding such as in benzene, C6H6

In general, multiple bonds are stronger (meaning harder to break) than single bonds:

In the section on bond enthalpy, we learn that we can measure the strengths of bonds in terms of the energy required to break them, and that the overall enthalpy change in forming a compound from its elements in the standard state is just the sum of all of the bond enthalpies.

It's easy to see in that table the general trend of increasing bond strength with number of electron pairs shared. We'll call that bond order in the section below.

Mostly, the stronger a covalent bond, the shorter it is — and it's true the other way around. Here are strengths (in KJ/mol) and lengths in Ångstroms (Å) (1 Å = 1 × 10-10m) of single, double and triple bonds of between carbon atoms:

| Bond type | Strength (KJ/mol) | Length (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| C — C | 347 | 1.54 |

| C = C | 614 | 1.34 |

| C ≡ C | 839 | 1.20 |

While all C—H bonds of methane (CH4) are and ought to be equivalent, they are not equivalent in this series showing the energy needed to remove the next H atom.

| reaction | ΔH (KJ/mol) |

|---|---|

| CH4 (g) → CH3 (g) + H(g) | 439 |

| CH3 (g) → CH2 (g) + H(g) | 462 |

| CH2 (g) → CH (g) + H(g) | 424 |

| CH (g) → C (g) + H(g) | 338 |

Notice in the table above that removing the last hydrogen takes less energy, and that removing the second takes the most. Rerrangements in the bonding geometry of CH4 and the resulting molecule after each successive removal account for the small differences in bond strength.

In the carbon-halogen series below, bond strengths and lengths are compared for C—F, C—Cl, C—Br and C—I bonds.

| Bond | Strength (KJ/mol) | Length (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| C—F | 439 | 1.35 |

| C—Cl | 330 | 1.77 |

| C—Br | 275 | 1.94 |

| C—I | 240 | 2.14 |

Here the bond strengths diminish with increasing bond length due to the size of the halogen atom.

In the series below, compare strengths of the bonds between fluorine, the most electronegative atom, and H, F, Cl, Br and I. The F-H bond is quite strong for a single bond because it only has one full shell of eight electrons (n = 2), which are all (including the single shared electron of the hydrogen atom) held tightly by the proximity of the fluorine nucleus.

| Bond | Strength (KJ/mol) | Length (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| F—H | 565 | |

| F—F | 155 | 1.42 |

| F—Cl | 249 | 1.66 |

| F—Br | 249 | 1.78 |

| F—I | 278 | 1.91 |

As we go down the series, two things happen. First, the bond length elongates because of the physical size of the halogen atom bound to the fluorine, and second, outer-shell electrons of those atoms are farther from the nucleus, making them less tightly bound.

Bond order

The order of a bond (bond order or sometimes bond number) is the number of electron pairs between two atoms in a compound. Bond order gives some indication of the strength of a bond, assuming that strength scales with the number of electrons involved in bonding.

For many compounds like H—H and Cl—Cl, bond order is straightforward; in each of these compounds one pair of electrons is shared, so the bond order is 1. Likewise in H2C=CH2, the bond order (between the carbon atoms) is two. In HC≡CH, the bond order between carbon atoms is three because a triple bond is the sharing of three pairs of electrons.

It's not quite so simple (but it is informative) for molecules in which there is some resonance between different kinds of bonds — something we learn about in our study of Lewis structures.

For example, look at the structure of benzene, C6H6:

Each C-C bond is a mixture of a double bond (order = 2) and a single bond (order = 1). We average the two to find the overall bond order is 1.5 or 3/2. The bond order, in this case, helps us to notice that the strength of this bond will likely lie somewhere between those of single and double C-C bonds.

Practice problems

Determine the order of each kind of bond in the molecules below. Roll-over or tap the image to see the solution.