There are a number of ways to learn about the important concepts of permutations and combinations. I'm going to lay out several examples using colored marbles and other things. I'll stop along the way and point out the laws of counting (permutations & combinations), then at the end we can think about how these examples extend into almost every aspect of our probability-driven universe.

First we should define these words, permutation and combination.

We're going to be talking about ways of counting things. A permutation is the number of ways that the same set of things can be arranged.

For example, the digits 1, 2, 3, can be arranged in six different ways:

![]()

It turns out that six is actually 3! (3-factorial, or 3 · 2 · 1), and that the number of ways of rearranging four distinct things, like the digits 1, 2, 3 and 4, is 4! = 24, but we'll get to that later.

Think of a combination as a sub-grouping of a larger group. For example, when you enter the lottery, you might be trying to pick the right combination of six numbers out of a pool of 40 integers, 1 - 40.

A permutation is a way of arranging n items in a set. For example, the number of ways of arranging n distinguishable items is n! = n · (n-1) · (n-2) · ... · 3 · 2 · 1.

A combination is a subgroup of a larger group. If there are 10 marbles in a bag, we can sample them randomly 1 at a time, 2 at a time, 3 at at time, ... and so on. Each way of sampling the larger group is a permutation from that group.

For our first example, let's consider a box filled with six marbles, three green (G) and three blue (B). We're going to blindly (randomly) draw a single marble from the box and look at some probabilities. We'll call the probability of drawing a green marble P(G) and the probability of drawing a blue marble P(B).

For our first experiment, let's say we draw a marble and put it back (replace it) before drawing another, and we'll do this ten times. Let's ask, what are the probabilities of drawing all green, one blue and 9 green, two blue an 8 green ... and so on up to all blue marbles. Here's how it works.

With an even number of B and G in the box, then the chance of drawing B or G is 50% or 0.5: P(B) = P(G) = 0.5.

The chance of drawing a green marble is P(G) = 0.5. Now we replace that marble, mix them up and draw again. The probability of getting another green marble is P(G) = 0.5. Here's the tricky part: The probability of drawing two green marbles, one after another is 0.5·0.5 = 0.25. – the probabilities multiply. We can keep up this kind of thinking to get the probability of drawing three greens in a row: 0.5 x 0.5 x 0.5 = 0.125, and we notice that the overall probability is just (0.5)n or P(G)n. So by extension, the probability of drawing ten green marbles in a row is P(G)10 = 0.510 = 0.000976 or 0.0976%, very low indeed, as we might expect.

Of course, we expect the probability of drawing ten blue marbles, with replacement and mixing of each afterward, to be the same.

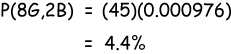

Now when we start thinking about mixed sets of outcomes of our 10-draw experiment, we have to be more careful. Let's calculate the probability of drawing 9 green and 1 blue marble out of ten draws, with replacement. The trick is that we haven't said that we care about which of the ten draws produces the blue marble. Therefore, any of these ten combinations would be OK:

Looking at the first combination, we see that the probability of drawing marbles like that is P(G)9·P(B)1 = 0.000976, the same as for drawing ten greens. The difference is that we don't care about which marble the blue turns out to be, only that there is one. Because we have ten total possibilities for nine greens and one blue, we have ten chances to get it, and to reflect that we have to improve our probability by a factor of ten – we multiply by 10, or more precisely, we multiply by the number of ways of achieving 9G + 1B:

$$P(9G, 1B) = n[P(G)^9 \cdot P(B)]$$

So our result is

$$ \begin{align} P(9G, 1B) &= 10(0.000976) \\ &= 0.00976 \\ &\approx 1 \, \% \\ \end{align}$$

which is ten times larger than P(10G) or P(10B).

Well, we can keep going with that to find the probabilities drawing all of the other combinations: three blue marbles, four and so on ... Here's a summary of the results (right →).

Notice that as we include more blue marbles, there are more ways to arrange all ten – up to 252 for 5 greens and 5 blues. That translates into a greater probability of choosing 5 and 5: More ways means a higher probability.

The number of ways of arranging k objects in a set of n objects is clearly very important in finding probabilities like this. What's left now is to find a better way of finding and expressing that number.

It's tempting at first to say that it must be 9! = 9 · 8 · 7 · 6 · 5 · 4 · 3 · 2 · 1 = 362,880, but that wouldn't be correct.

Look at the word. If I swapped the first and second letter B, could you tell the difference ? If not, is that really a rearrangement of the word ? Moreover, there are three B's in the word, and for any given overall arrangement of BUMBLEBEE, like BEELBMUBE, there are 3! = 6 ways of rearranging those. It's worse when we look at the E's. There are four.

Our original notion, 9! was fine, but it has to be reduced by the number of ways of rearranging the B's and the E's, like this:

That's still a big number, but it's accurate. It reflects that there is a very large number of ways of arranging 9 things, but that if some of these are identical, that number is reduced.

In general, we say that the number of distinguishable combinations of n elements with sets of indistinguishable elements n1, n2, ... is

![]()

Now lets relate the number of ways of writing BUMBLEBEE to the probability of getting any one combination by drawing the numbers randomly. It's just 1 "in" that number, or 1/2,520. The probability is the reciprocal of the number of ways of arranging the letters.

So the probability of randomly landing on the arrangement BEELBMUBE of the letters of BUMBLEBEE is 1/2,520 or 0.04%.

The probability of randomly obtaining an arrangement of n things is the inverse of the number distinguishable combinations of those things.

The alphabet contains 26 non-repeating (distinguishable) elements. The number of possible permutations of the alphabet is 26! = 4 x 1026. That's huge!

Now there are 26 choices for the first letter, 25 for the second and 23 for the third, so the number of possible combinations is 26·25·24 = 15,600. Another way to look at it is that when we draw only three letters, we leave 23 letters behind. We can express the number of combinations of three letters from a set of 26 like this:

In general we express the number of combinations of n items, taken k at a time (26 taken 3 at a time in our example) like this:

![]()

The part in parenthesis is called a binomial coefficient, and we read it as "n, choose k". It means that we're choosing a subset of k elements out of a set of n distinguishable elements. The n! on top is the number of ways of arranging n elements, and the (n-k)! in the denominator divides out all of those arrangements of the remaining letter not chosen. You should convince yourself that this is the right way to express the result of the above experiment.

Well ... that's up to you. If it does, then the expression above is OK. In other words, we choose to distinguish ABC from ACB from BCA, and so on.

But if order does not matter, we have to reduce the number of ways by dividing by k!. It looks like this:

![]()

![]()

xaktly.com by Dr. Jeff Cruzan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. © 2012, Jeff Cruzan. All text and images on this website not specifically attributed to another source were created by me and I reserve all rights as to their use. Any opinions expressed on this website are entirely mine, and do not necessarily reflect the views of any of my employers. Please feel free to send any questions or comments to jeff.cruzan@verizon.net.