Finding volumes of 3-D objects with circular symmetry in at least one dimension

Finding volumes of strange shapes can be very easy if those shapes are volumes of revolution. Such objects are formed by taking any open or closed planar curve and revolving it by some angle (usually 2π rad = 360˚) around some axis (any axis, actually, but we'll generally use one of the Cartesian axes).

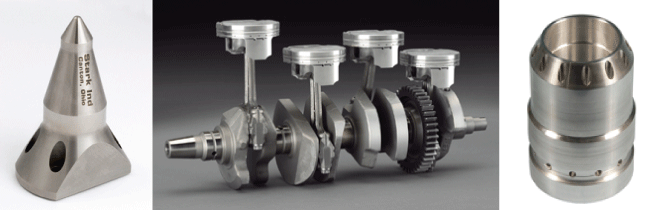

Many objects we use and engineer are actually manufactured in this way, by "turning" a piece of material on a lathe to make a shape with a round profile in one of its dimensions. Think of a bolt or screw, or a pipe. Here are some other examples of objects with at least some circular symmetry.

Generating a solid of revolution

The cartoon below illustrates how solid of revolution is generated from a plane curve. The curve $f(x)$ (black) is shown in the left-hand panel. If we revolve $f(x)$ around the $y$-axis 1/4 of the way around the blue circle, we get the shape in the second panel. Think of it as one fourth of the full "goblet"

shape on the far right. Likewise, rotations of 180˚ and 360˚ give us half a goblet and the full shape. Put a stem on it and it's a nice wine glass. In this section we'll learn how to calculate volumes of figures obtained be this kind of revolution of a 2-D curve.

How we'll find the volumes

We can approximate the volume of a solid with circular cross sections (a circularly-symmetric solid) by stacking up cylinders of varying radius. We know how to calculate the volume of a cylinder, so a stack of cylinders is easy, too. In the center figure below, six cylinders are a rough approximation of our green "cup."

On the right, notice that 12 cylinders of height Δy is a better approximation. The approximate volume will just be the sum of a collection of n cylinders:

$$V \approx \sum_{i = 1}^n \pi r^2 \Delta y,$$

where r is given by the distance of the function from (in this case) the $y$-axis, and $\Delta y$ is the height of each cylinder or disk.

Now it's not a great leap to imagine that we shrink the height of our cylinders down to an infinitessimally small height, dy, and sum the volumes of an infinite number of them in a definite integral:

$$V = \int_a^b \pi r^2 \, dy,$$

where a and b are the limits of integration, in this example along the y-axis. In the examples below, we'll figure out how to find r as a function of which-ever variable is our independent variable.

The best way to illustrate finding volumes by the disk method is by example. At the end, we'll try to capture all of the steps and make sense of them.

Example 1 – Volume of a sphere

As a first example , let's calculate the volume of a sphere of radius $R$. Of course, we already know the answer,

$$V = \frac{4}{3} \pi R^3$$

so we'll be able to check our result.

Any sphere can be approximated by a stack of appropriately-sized disks, as shown on the left. The volume of each disk is $\pi r^2 \Delta x$, where $r$ is the radius of the specific disk and $\Delta x$ is its height.

Then as we do with calculus, we let the width of each disk approach zero, replacing $\Delta x$ with the infinitesimal width $dx$, and summing over an infinite number of disks, to get the integral

There are two crucial steps to the problem. The first is getting the integrand correct, and we're part way there - we have to get $A(x)$. The second is the limits of integration. Here it's pretty easy to see that for a sphere of radius $R$ conveniently centered at $(0, 0)$, the limits are $-R$ to $R$.

From the geometry shown on the left, we just use the Pythagorean theorem to show that $r^2=R^2-x^2$, the area as a function of #X#. Note that $R$ is a parameter of this problem. We'd just plug in whatever value of $R$ we need for the sphere we're using.

Now our integral and its solution are reasonably straightforward:

$$ \begin{align} V &= \pi \int_{-R}^R (R^2 - x^2) \, dx \\[5pt] &= \pi \left( R^2 x - \frac{x^3}{3} \right) \bigg|_{-R}^R \\[5pt] &= \pi \left( 2 R^3 - \frac{2R^3}{3} \right) = \bf \frac{4}{3}\pi R^3 \end{align}$$

Example 2 – Integration along the y-axis

Sometimes it's easier to set up these problems so that we integrate along the y-axis instead of x. One example is the volume enclosed by revolving the parabola $y=x^2$ about the y-axis between $x=0$ and $x=4$, as shown on the right.

The disks are horizontal this time, but the geometry is very simple. The radius of each disk is $x$, but because we're integrating along the y-axis, we express $x$ in terms of $y$. We actually want $x^2$ (the radius squared) so this couldn't be easier: $y = x^2$.

$$V = \int_0^4 \pi y \, dy$$

Now the easy integral is:

$$ \begin{align} V \int_0^4 \pi y \, dy &= \frac{\pi y^2}{2} \bigg|_0^4 \\[5pt] &= \frac{\pi}{2} (4^2 - 0^2) = 8\pi \; \text{units}^3 \end{align}$$

... which is about 25 cubic units.

Example 3

In this example, we revolve the quadratic function $f(x) = (x-3)^2 + 1$ around the $x$ axis and calculate the volume of the resulting figure between $x = 0$ and $x = 5$.

Because this is a volume of revolution, we can place disks of width $dx$ perpendicular to the $x$-axis, and integrate along $x$.

The radius of each disk is $f(x)$, so the volume of each is $\pi[f(x)]^2$ or $ \pi[(x-3)^2]$ If we integrate between the limits of $x=0$ and $x=5$, we get:

$$ \begin{align} V &= \pi \int_0^5 [(x - 3)^2 + 1]^2 \, dx \\[5pt] &= \pi \int_0^5 (x^4 - 23x^3 + 56x^2 - 120x + 100) \, dx \\[5pt] &= \pi \left( \frac{x^5}{5} - 3x^4 + \frac{56x^3}{3} - 60x^2 + 100x \right) \bigg|_0^5 \\[5pt] &= \bf 83.3\pi \; units^3 \end{align}$$

Steps for finding volumes of revolution using disks

- Figure out the geometry of the problem. Is the figure one for which the disk method will work? Will you integrate along $x$ or $y$ (or another axis) ?

- Find the area of a single disk using geometry and the function.

- Find the limits of integration.

- Integrate between the limits along the axis perpendicular to the disks.

Volume of revolution by the disk method

$$V = \int_a^b A(x) \, dx \; = \; \pi \int_a^b [r(x)]^2 \, dx$$

where $A(x)$ is the area of a disk and $x$ is the coordinate along which the integration is performed, and $dx$ is the width of the disk along that coordinate.

Example 4 – Shifting the axis of revolution

Calculate the volume of the solid generated by revolving the part of $f(x) = x^3$ about the line $x = 1$ and between $y = 1$ and $y = 6.$

Now we need to find the radius of our disk, labeled x above, but that's a little trickier. First we're integrating along the y-axis, so we'll need $x(y) = y^{1/3},$ which gives us the x-distance from the origin as we move along the y-axis. Next, the radius of our disk will be one minus that x-value.

$$r = 1 - y^{1/3}$$

Then the volume of each disk will be

$$V_{disk} = \pi r^2 \, dy = \pi (1 - y^{1/3})^2 \, dx$$

Now our integral and its solution are

$$ \begin{align} A &= \int_1^6 (1 - y^{1/3})^2 \, dy \\[5pt] &= \int_1^6 (1 - 2 y^{1/3} + y^{2/3}) \, dy \\[5pt] &= y - 2 \frac{3}{4} y^{4/3} + \frac{3}{5} y^{5/3} \bigg|_1^6 \\[5pt] &= 6 - \frac{3}{2} \cdot 6^{4/3} + \frac{3}{5} 6^{5/3} - 1 + \frac{3}{2} - \frac{3}{5} \\[5pt] &= 6 - 16.35 + 11.88 - 1 + 1.5 - 0.6 \\[5pt] &= 1.43 \; units^3 \end{align}$$

Here's a picture of the revolved figure to help you visualize it.

Pro tip:

The most tedious part of integrals like these is often evaluating the limits. Take your time and take care to simplify and group terms when possible.

Practice problems

-

When the region bounded by $y = 2x, \; y = 3$ and the $y$-axis is revolved around the $y$-axis, a cone is generated. Find the volume of the cone using geometry $\left( V = \frac{1}{3}\pi r^2 h \right)$ and by using the disk method.

Solution

There's no substitute for sketching a diagram in these problems. do that first.

Figure out the cross-sectional area and the volume of each disk:

$$ \begin{align} A_{disk} &= \pi \left(\frac{y}{2}\right)^2 = \frac{\pi}{4} y^2 \\[5pt] V_{disk} &= \frac{\pi}{4} y^2 \, dy \end{align}$$

Now do the integral to find the volume:

$$ \begin{align} V &= \pi \frac{\pi}{4} \int_0^3 y^2 \, dy = \frac{\pi}{4} \left( \frac{y^3}{3} \right) \bigg|_0^3 \\[5pt] V &= \frac{\pi}{12} (3^3 - 0^3) = \bf \frac{27\pi}{12} \; units^3 \approx 7.1 \; units^3 \end{align}$$

-

The region bounded by $y = \sqrt{x}, \; x = 5,$ and the x-axis is revolved about the $x-axis$. Calculate the volume of the resulting solid.

Solution

There's no substitute for sketching a diagram in these problems. do that first.

Figure out the cross-sectional area and the volume of each disk:

$$ \begin{align} A_{disk} &= \pi (\sqrt{x})^2 = \pi x \\[5pt] V_{disk} &= \pi x \, dx \end{align}$$

Now do the integral to find the volume:

$$ \begin{align} V &= \pi \int_0^5 x \, dx = \frac{\pi x^2}{2} \bigg|_0^5 \\[5pt] V &= \bf \frac{25\pi}{2} \; units^3 \end{align}$$

-

Calculate the volume of the solid that results when the region in the first quadrant between $y = sin(x)$ and $y = cos(x)$ is revolved about the y-axis.

Solution

Always sketch a diagram first.

Figure out the cross-sectional area and the volume of each disk:

$$ \begin{align} A_{disk} &= \pi (\sqrt{x-1})^2 = \pi (x - 1) \\[5pt] V_{disk} &= \pi (x - 1)^2 \, dx \end{align}$$

Now do the integral to find the volume:

$$ \begin{align} V &= \pi \int_1^5 (x - 1) \, dx = \left( \frac{\pi x^2}{2} - x \right) \bigg|_1^5 \\[5pt] V &= \pi \left[ \left( \frac{25}{2} - 5 \right) - \left( \frac{1}{2} - 1 \right) \right] \\[5pt] &= \pi \left[ \frac{25}{2} - \frac{1}{2} - 5 + 1 \right] \\[5pt] &= \pi \left[ \frac{24}{2} - 4 \right] \\[5pt] &= \pi(12 - 4) = 8\pi \; units^3 \end{align}$$

-

Find the volume of the solid generated by revolving the region between $y = (x - 1)^{1/2}, \; x = 5$ and the $x$-axis around the $x$-axis.

Solution

Always sketch a diagram first.

Figure out the cross-sectional area and the volume of each disk:

$$ \begin{align} A_{disk} &= \pi y^2 = \pi (\sqrt{x^2 - 1})^2 = \pi(x^2 - 1)\\[5pt] V_{disk} &= \pi(x^2 - 1) \, dx \end{align}$$

Now do the integral to find the volume:

$$ \begin{align} V &= \pi \int_1^2 (x^2 - 1) \, dx = \pi \left[ \frac{x^3}{3} - x \right]_1^2 \\[5pt] &= \pi \left[ \frac{8}{3} - 2 - \frac{1}{3} + 1 \right] \\[5pt] &= \pi \left[ \frac{7}{3} - \frac{3}{3} \right] \\[5pt] &= \bf \frac{4 \pi}{3} \; units^3 \end{align}$$

-

Calculate the volume of the solid generated by revolved the region between $x^2 - y^2 = 1$& and $x = 2$ about the x-axis.

Solution

Solution

Video examples

1. Volume of revolution | Disk method (x-axis)

Minutes of your life: 2:14

2. Volume of revolution | Disk method

Minutes of your life: 4:01

Cartesian

The Cartesian coordinate system, devised by French mathematician and philosopher Rene Descartes (1596-1650), is the most frequently used 2-dimensional graphing system. The vertical axis (y) is oriented 90˚ from the horizontal (x) axis, and any point on the Cartesian plane has coordinates (x, y).

![]()

xaktly.com by Dr. Jeff Cruzan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. © 2012-2025, Jeff Cruzan. All text and images on this website not specifically attributed to another source were created by me and I reserve all rights as to their use. Any opinions expressed on this website are entirely mine, and do not necessarily reflect the views of any of my employers. Please feel free to send any questions or comments to jeff.cruzan@verizon.net.